What Is the Correct Name of the Original Japanese Art of Jujutsu?

Japanese martial arts refer to the multifariousness of martial arts native to the country of Japan. At least three Japanese terms are used interchangeably with the English language phrase Japanese martial arts.

The usage of term budō to hateful martial arts is a modern i and historically the term meant a fashion of life encompassing physical, spiritual and moral dimensions with a focus of self-improvement, fulfillment or personal growth.[i] The terms bujutsu and bugei have unlike meanings from budo, at least historically speaking. Bujutsu refers specifically to the practical awarding of martial tactics and techniques in bodily combat.[2] Bugei refers to the adaptation or refinement of those tactics and techniques to facilitate systematic instruction and dissemination inside a formal learning environment.[2]

| Term | Translation |

|---|---|

| budō ( 武道 ) | martial way [3] [4] [5] |

| bujutsu ( 武術 ) | martial technique alternatively science, art or arts and crafts of war |

| bugei ( 武芸 ) | martial art |

History [edit]

Disarming an assailant using a tachi-dori ("sword-taking") technique.

The historical origin of Japanese martial arts tin exist found in the warrior traditions of the samurai and the caste arrangement that restricted the employ of weapons by other members of club. Originally, samurai were expected to be practiced in many weapons, as well as unarmed combat, and attain the highest possible mastery of combat skills.

Ordinarily, the development of combative techniques is intertwined with the tools used to execute those techniques. In a quickly irresolute world, those tools are constantly changing, requiring that the techniques to use them be continuously reinvented. The history of Nippon is somewhat unusual in its relative isolation. Compared with the residual of the world, the Japanese tools of war evolved slowly. Many people believe that this afforded the warrior course the opportunity to report their weapons with greater depth than other cultures. Nevertheless, the instruction and training of these martial arts did evolve. For example, in the early on medieval period, the bow and the spear were emphasized, but during the Tokugawa menstruum (1603-1867 CE), fewer large scale battles took identify, and the sword became the about prestigious weapon. Some other tendency that developed throughout Japanese history was that of increasing martial specialization equally lodge became more than stratified over fourth dimension.[6]

The martial arts developed or originating in Japan are extraordinarily diverse, with vast differences in training tools, methods, and philosophy across innumerable schools and styles. That said, Japanese martial arts may generally be divided into koryū and gendai budō based on whether they existed prior to or after the Meiji Restoration (1868), respectively.[ citation needed ] Since gendai budō and koryū often share the same historical origin,[ commendation needed ] one will discover various types of martial arts (such as jujutsu, kenjutsu, or naginatajutsu) on both sides of the divide.

- A note on the organization of this article; it would be incommunicable to hash out Japanese martial arts in terms of the thousands of individual schools or styles, such as Ittō-ryū, Daitō-ryū, or Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū. Instead, major sections are divided based on when the art originated (regardless of whether it is nevertheless practiced), and subsections are dedicated to the root type of martial art, such as jujutsu (the art of empty-handed gainsay through use of indirect application of force) or kendo (Japanese sport fencing), wherein notable styles or major differences between styles may exist discussed.

Koryū bujutsu [edit]

Koryū ( 古流:こりゅう ), significant "traditional school", or "one-time school", refers specifically to schools of martial arts, originating in Japan, either prior to the beginning of the Meiji Restoration in 1868, or the Haitōrei edict in 1876.[7] In modern usage, bujutsu ( 武術 ), meaning military art/science, is typified by its practical application of technique to existent-world or battlefield situations.

The term also is used generally to indicate that a item fashion or art is "traditional", rather than "modernistic". However, what it means for an art to be either "traditional" or "modernistic" is subject to some debate. As a dominion of thumb, the master purpose of a koryū martial art was for use in war. The most extreme example of a koryū school is one that preserves its traditional, and often ancient, martial practices fifty-fifty in the absence of standing wars in which to test them. Other koryū schools may have made modifications to their practices that reflect the passage of time (which may or may non accept resulted in the loss of "koryū" status in the eyes of its peers). This is equally opposed to "modern" martial arts, whose chief focus is more often than not upon the self-comeback (mental, concrete, or spiritual) of the individual practitioner, with varying degrees of emphasis on the applied application of the martial fine art for either sport or self-defence purposes.[ citation needed ]

The following subsections stand for not individual schools of martial arts, but rather generic "types" of martial arts. These are generally distinguishable on the footing of their training methodology and equipment, though wide variation withal exists inside each.

Sumo [edit]

Sumo ( 相撲:すもう , sumō ), considered past many to be Nippon's national sport, has its origins in the distant past. The earliest written records of Nippon, which are dated from the 8th century Advert, record the first sumo friction match in 23 BC, occurring specifically at the request of the emperor and continuing until one man was too wounded to continue[ citation needed ]. Beginning in 728 AD, the Emperor Shōmu (聖武天皇, 701–756) began holding official sumo matches at the annual harvest festivals. This tradition of having matches in the presence of the emperor connected, but gradually spread, with matches also held at Shinto festivals, and sumo grooming was somewhen incorporated into military training. By the 17th century, sumo was an organized professional sport, open up to the public, enjoyed by both the upper class and commoners.

Today, sumo retains much of its traditional trappings, including a referee dressed as a Shinto priest, and a ritual where the competitors clap hands, stomp their feet, and throw salt in the ring prior to each match. To win a match, competitors utilise throwing and grappling techniques to strength the other man to the ground; the start man to affect the footing with a part of the body other than the bottom of the feet, or touch the basis outside the ring with whatsoever part of the body, loses. Six g tournaments are held annually in Japan, and each professional person fighter'due south name and relative ranking is published after each tournament in an official list, called the banzuke, which is followed religiously by sumo fans.

Jujutsu [edit]

Jujutsu training at an agronomical school in Japan around 1920.

Jujutsu ( 柔術:じゅうじゅつ , jūjutsu ), literally translates to "Soft Skills". Yet, more accurately, it means the fine art of using indirect strength, such equally joint locks or throwing techniques, to defeat an opponent, as opposed to straight strength such every bit a punch or a kick. This is non to imply that jujutsu does not teach or employ strikes, but rather that the art'due south aim is the power to use an assailant's force against him or her, and counter-attack where they are weakest or least defended.

Methods of combat included hitting (kicking, punching), throwing (trunk throws, joint-lock throws, unbalance throws), restraining (pinning, strangulating, grappling, wrestling) and weaponry. Defensive tactics included blocking, evading, off balancing, blending and escaping. Minor weapons such as the tantō (dagger), ryufundo kusari (weighted chain), jutte (helmet smasher), and kakushi buki (secret or disguised weapons) were almost always included in koryū jujutsu.

About of these were battlefield-based systems to be practiced equally companion arts to the more common and vital weapon systems. At the time, these fighting arts went by many dissimilar names, including kogusoku, yawara, kumiuchi, and hakuda. In reality, these grappling systems were non actually unarmed systems of combat, but are more accurately described every bit means whereby an unarmed or lightly armed warrior could defeat a heavily armed and armored enemy on the battlefield. Ideally, the samurai would be armed and would not need to rely on such techniques.[ citation needed ]

In later times, other koryū adult into systems more familiar to the practitioners of the jujutsu commonly seen today. These systems are more often than not designed to deal with opponents neither wearing armor nor in a battleground environment. For this reason, they include extensive use of atemi waza (vital-striking technique). These tactics would be of piddling use against an armored opponent on a battleground. They would, all the same, be quite valuable to anyone against an enemy or opponent during peacetime dressed in normal street attire. Occasionally, camouflaged weapons such as knives or tessen (fe fans) were included in the curriculum.[ citation needed ]

Today, jujutsu is skilful in many forms, both ancient and modern. Diverse methods of jujutsu have been incorporated or synthesized into judo and aikido, as well as beingness exported throughout the world and transformed into sport wrestling systems, adopted in whole or role by schools of karate or other unrelated martial arts, still skillful as they were centuries ago, or all of the above.

Swordsmanship [edit]

A matched ready (daisho) of antique Japanese (samurai) swords and their individual mountings (koshirae), katana on top and wakisashi beneath, Edo menstruum.

Swordsmanship, the art of the sword, has an almost mythological ethos, and is believed by some to be the paramount martial fine art, surpassing all others. Regardless of the truth of that belief, the sword itself has been the discipline of stories and legends through nigh all cultures in which it has been employed as a tool for violence. In Nihon, the use of the katana is no dissimilar. Although originally the most important skills of the warrior course were proficiency at horse-riding and shooting the bow, this somewhen gave manner to swordsmanship. The earliest swords, which can exist dated as far back every bit the Kofun era (third and 4th centuries) were primarily directly bladed. According to fable, curved swords fabricated stiff by the famous folding process were beginning forged by the smith Amakuni Yasutsuna (天國 安綱, c. 700 AD).[8]

The primary development of the sword occurred between 987 Advertizing and 1597 Advertising. This evolution is characterized by profound artistry during peaceful eras, and renewed focus on durability, utility, and mass production during the intermittent periods of warfare, most notably ceremonious warfare during the 12th century and the Mongolian invasions during the 13th century (which in particular saw the transition from mostly horseback archery to hand to hand ground fighting).

This evolution of the sword is paralleled by the development of the methods used to wield it. During times of peace, the warriors trained with the sword, and invented new ways to implement it. During state of war, these theories were tested. After the war ended, those who survived examined what worked and what didn't, and passed their knowledge on. In 1600 Advert, Tokugawa Ieyasu (徳川 家康, 1543–1616) gained full control of all of Japan, and the country entered a period of prolonged peace that would last until the Meiji Restoration. During this menses, the techniques to use the sword underwent a transition from a primarily utilitarian fine art for killing, to one encompassing a philosophy of personal development and spiritual perfection.

The terminology used in Japanese swordsmanship is somewhat ambiguous. Many names have been used for various aspects of the art or to embrace the art equally a whole.

Kenjutsu [edit]

Kenjutsu ( 剣術:けんじゅつ ) literally ways "the art/science of the sword". Although the term has been used equally a full general term for swordsmanship as a whole, in mod times, kenjutsu refers more than to the specific aspect of swordsmanship dealing with partnered sword training. Information technology is the oldest grade of preparation and, at its simplest level, consists of two partners with swords drawn, practicing combat drills. Historically skilful with wooden katana (bokken), this about often consists of pre-adamant forms, chosen kata, or sometimes chosen kumitachi, and similar to the partner drills expert in kendo. Among advanced students, kenjutsu training may too include increasing degrees of freestyle practice.

Battōjutsu [edit]

Battōjutsu ( 抜刀術:ばっとうじゅつ ), literally meaning "the art/science of cartoon a sword", and developed in the mid-15th century, is the aspect of swordsmanship focused upon the efficient depict of the sword, cut down i's enemy, and returning the sword to its scabbard (saya). The term came into use specifically during the Warring States Menstruum (15th–17th centuries). Closely related to, but predating iaijutsu, battōjutsu grooming emphasizes defensive counter-attacking. Battōjutsu grooming technically incorporates kata, but mostly consist of only a few moves, focusing on stepping up to an enemy, drawing, performing i or more cuts, and capsule the weapon. Battōjutsu exercises tend to lack the elaborateness, besides every bit the aesthetic considerations of iaijutsu or iaidō kata.[ citation needed ] Finally, note that use of the name alone is not dispositive; what is battōjutsu to i school may be iaijutsu to another.[ citation needed ]

Iaijutsu [edit]

Iaijutsu ( 居合術:いあいじゅつ ), approximately "the art/scientific discipline of mental presence and immediate reaction", is also the Japanese art of cartoon the sword. Nevertheless, unlike battōjutsu, iaijutsu tends to be technically more than complex, and in that location is a much stronger focus upon perfecting course. The primary technical aspects are smooth, controlled movements of drawing the sword from its scabbard, striking or cut an opponent, removing blood from the blade, and then replacing the sword in the scabbard.

Naginatajutsu [edit]

A samurai wielding a naginata.

Naginatajutsu ( 長刀術:なぎなたじゅつ ) is the Japanese art of wielding the naginata, a weapon resembling the medieval European glaive or guisarme. Almost naginata practice today is in a modernized form (gendai budō) called the "mode of naginata" (naginata-dō) or "new naginata" (atarashii naginata), in which competitions are too held.

However, many koryu maintain naginatajutsu in their curriculum. Also of annotation, during the late Edo period, naginata were used to train women and ladies in waiting. Thus, almost naginatajutsu styles are headed by women and most naginata practitioners in Japan are women. This has led to the impression overseas that naginatajutsu is a martial art that was not used by male warriors. In fact, naginatajutsu was developed in early medieval Japan and for a time was widely used past samurai.[ citation needed ]

Sōjutsu [edit]

Sōjutsu ( 槍術:そうじゅつ ) is the Japanese art of fighting with the spear (yari). For well-nigh of Nihon's history, sōjutsu was practiced extensively by traditional schools. In times of state of war, it was a primary skill of many soldiers. Today information technology is a modest art taught in very few schools.

Shinobi no jutsu [edit]

Shinobi no jutsu (aka Ninjutsu) was adult by groups of people mainly from Iga, Mie and Kōka, Shiga of Japan who became noted for their skills every bit infiltrators, scouts, secret agents, and spies. The preparation of these shinobi (ninja) involves espionage, sabotage, disguise, escape, concealment, assassination, archery, medicine, explosives, poisons, and more.

Other koryū martial arts [edit]

The early martial fine art schools of Nihon were almost entirely "Sōgō bujutsu", blended martial systems made up of an eclectic collection of skills and tools. With the long peace of the Tokugawa shogunate there was an increase in specialization with many schools identifying themselves with item major battleground weapons. However, there were many boosted weapons employed past the warriors of feudal Nippon, and an art to wielding each. Usually they were studied as secondary or tertiary weapons within a school merely there are exceptions, such as the art of wielding the brusk staff, (jōdō) which was the primary fine art taught by the Shintō Musō-ryū.

Other arts existed to teach military skills other than the use of weaponry. Examples of these include marine skills such as swimming and river-fording (suijutsu), equestrianism (bajutsu), arson and demolition (kajutsu).

Gendai budō [edit]

Gendai budō ( 現代武道:げんだいぶどう ), literally pregnant "modern martial way",[ citation needed ] usually applies to arts founded later on the beginning of the Meiji Restoration in 1868.[ citation needed ] Aikido and judo are examples of gendai budō that were founded in the mod era, while iaidō represents the modernization of a practice that has existed for centuries.

The core departure is, every bit was explained nether "koryū", above, that koryū arts are practiced as they were when their primary utility was for use in warfare, while the main purpose of gendai budō is for cocky-improvement, with self-defense force every bit a secondary purpose. Additionally, many of the gendai budō accept included a sporting chemical element to them. Judo and kendo are both examples of this.

Judo [edit]

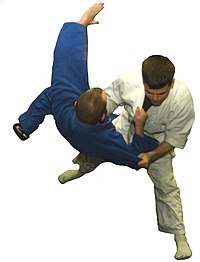

Judoka executing a throw (o-soto-gari).

Judo ( 柔道:じゅうどう , jūdō ), literally meaning "gentle way" or "fashion of softness", is a grappling-based martial fine art, good primarily as a sport. It contains substantially the same emphasis on the personal, spiritual, and physical self-improvement of its practitioners every bit can be plant throughout gendai budō.

Judo was created by Kano Jigoro (嘉納 治五郎 Kanō Jigorō, 1860–1938) at the terminate of the 19th century. Kano took the koryū martial arts he learned (specifically Kitō-ryū and Tenjin Shin'yo-ryū jujutsu), and systematically reinvented them into a martial art with an emphasis on freestyle practice (randori) and contest, while removing harmful jujutsu techniques or limiting them to the kata. Kano devised a powerful organisation of new techniques and training methods, which famously culminated on June eleven, 1886, in a tournament that would afterwards be dramatized by historic Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa (黒沢 明 Kurosawa Akira, 1910–1998), in the film "Sanshiro Sugata" (1943).

Judo became an Olympic sport in 1964, and has spread throughout the globe. Kano Jigoro's original school, the "Kodokan", has students worldwide, and many other schools have been founded by Kano's students.

Kendo [edit]

Kendo grooming at an agricultural school in Japan effectually 1920.

Kendo ( 剣道:けんどう , kendō ), pregnant the "way of the sword", is based on Japanese sword-fighting.[ citation needed ] Information technology is an evolution of the art of kenjutsu, and its exercises and do are descended from several particular schools of swordsmanship. The master technical influence in its development was the kenjutsu school of Ittō-ryū (founded c. 16th century), whose core philosophy revolved effectually the concept that all strikes in swordsmanship revolve around the technique kiri-oroshi (vertical downward cut). Kendo actually began to have shape with the introduction of bamboo swords, called shinai,[ commendation needed ] and the prepare of lightweight wooden armour, called bōgu, by Naganuma Sirōzaemon Kunisato (長沼 四郎左衛門 国郷, 1688–1767), which allowed for the practice of strikes at full speed and ability without chance of injury to the competitors.[ citation needed ]

Today, virtually the entire[ citation needed ] practice of kendo is governed past the All Japan Kendo Federation, founded in 1951. Competitions are judged by points, with the offset competitor to score two points on their opponent declared the winner. 1 point may be scored with a successful and properly executed strike to any of several targets: a thrust to the throat, or a strike to the top of the head, sides of the caput, sides of the body, or forearms. Practitioners as well compete in forms (kata) competitions, using either wooden or blunted metallic swords, according to a gear up of forms promulgated by the AJKF.[ commendation needed ]

Iaidō [edit]

Iaidō ( 居合道:いあいどう ), which would be "the way of mental presence and immediate reaction", is nominally the modernization of iaijutsu, but in exercise is ofttimes identical to iaijutsu.[ citation needed ] The replacement of jutsu with dō is part of the 20th century emphasis upon personal and spiritual development;[ commendation needed ] an evolution that took place in many martial arts.[ commendation needed ] In the case of iaidō, some schools only inverse in name without altering the curriculum, and others embraced the wholesale change from a combat-orientation to spiritual growth. Similar to Kendō, Iaidō is largely practiced under the All Japan Kendo Federation and it's not unusual for a Kendō order to offering Iaidō practice as well.

Aikido [edit]

Aikido shihōnage technique.

Aikido ( 合氣道:あいきどう , aikidō ) means "the way to harmony with ki". It is a Japanese martial art developed by Morihei Ueshiba (植芝 盛平 Ueshiba Morihei, 1883 – 1969). The art consists of "hitting", "throwing" and "joint locking" techniques and is known for its fluidity and blending with an assailant, rather than meeting "force with forcefulness". Emphasis is upon joining with the rhythm and intent of the opponent in order to detect the optimal position and timing, when the opponent can be led without force. Aikidō is also known for emphasizing the personal development of its students, reflecting the spiritual groundwork of its founder.

Morihei Ueshiba developed aikido mainly from Daitō-ryū aiki-jūjutsu incorporating training movements such as those for the yari (spear), jō (a short quarterstaff), and peradventure also juken (bayonet). Arguably the strongest influence is that of kenjutsu and in many means, an aikidō practitioner moves equally an empty handed swordsman.

Kyūdō [edit]

Kyūdō ( 弓道:きゅうどう ), which means "fashion of the bow", is the modern name for Japanese archery. Originally in Japan, kyujutsu, the "art of the bow", was a discipline of the samurai, the Japanese warrior class. The bow is a long range weapon that allowed a military unit to engage an opposing strength while information technology was even so far away. If the archers were mounted on horseback, they could exist used to even more devastating effect as a mobile weapons platform. Archers were too used in sieges and ocean battles.

However, from the 16th century onward, firearms slowly displaced the bow every bit the dominant battlefield weapon. As the bow lost its significance as a weapon of war, and nether the influence of Buddhism, Shinto, Daoism and Confucianism, Japanese archery evolved into kyudō, the "way of the bow". In some schools kyudō is practiced as a highly refined contemplative practice, while in other schools information technology is skilful as a sport.

Karate [edit]

Karate ( 空手 , karate ) literally means "empty hand". It is also sometimes called "the way of the empty manus" ( 空手道 , karatedō ). It was originally called 唐手 ("Chinese hand"), too pronounced 'karate'.

Karate originated in and, is technically, Okinawan, except for Kyokushin (an amalgamation of parts of Shotokan and Gojoryu), formerly known as the Ryūkyū Kingdom, simply now a role of present-day Japan. Karate is a fusion of pre-existing Okinawan martial arts, called "te", and Chinese martial arts. It is an art that has been adopted and developed past practitioners on the Japanese primary island of Honshu.

Karate's route to Honshu began with Gichin Funakoshi (船越 義珍 Funakoshi Gichin, 1868–1957), who is called the father of karate, and is the founder of Shotokan karate. Although some Okinawan karate practitioners were already living and teaching in Honshū, Funakoshi gave public demonstrations of karate in Tokyo at a concrete pedagogy exhibition sponsored by the ministry of instruction in 1917, and once more in 1922. As a upshot, karate preparation was subsequently incorporated into Nippon's public school arrangement. It was also at this time that the white uniforms and the kyū/dan ranking organization (both originally implemented by judo'due south founder, Kano Jigoro) were adopted.

Karate practice is primarily characterized by linear punching and kick techniques executed from a stable, fixed stance. Many styles of karate practiced today contain the forms (kata) originally adult by Funakoshi and his teachers and many different weapons traditionally concealed as farm implements by the peasants of Okinawa. Many karate practitioners too participate in lite- and no-contact competitions while some (ex. kyokushin karate) still compete in full-contact competitions with little or no protective gear.

Shorinji Kempo [edit]

Shorinji Kempo ( 少林寺拳法 , shōrinji-kenpō ) is a post-World War 2 system of self-defence and self-comeback training (行: gyo or field of study) known as the modified version of Shaolin Kung Fu. There are two primary technique categories such equally gōhō (strikes, kicks and blocks) and jūhō (pins, joint locks and dodges). It was established in 1947 past Doshin So ( 宗 道臣 , Sō Dōshin ) who had been in Manchuria during World War II and who on returning to his native Japan afterward Globe War II saw the demand to overcome the destruction and re-build self-conviction of the Japanese people on a massive calibration.

Although Shorinji Kempo was originally introduced in Nihon in the tardily 1940s and 1950s through large scale programmes involving employees of major national organizations (e.g. Japan Railways) it subsequently became pop in many other countries. Today, according to the World Shorinji Kempo Organization (WSKO),[9] there are almost 1.5 million practitioners in 33 countries.

Philosophical and strategic concepts [edit]

Aiki [edit]

The principle of aiki ( 合気 ) is especially hard to describe or explain. The most unproblematic translation of aiki, as "joining energy", belies its philosophical depth. More often than not, it is the principle of matching your opponent in social club to defeat him. Information technology is this concept of "matching", or "joining", or even "harmonizing" (all valid interpretations of ai) that contains the complexity. I may "match" the opponent in a clash of force, possibly even resulting in a mutual kill. This is not aiki. Aiki is epitomized by the notion of joining physically and mentally with the opponent for the express purpose of avoiding a straight clash of force. In practice, aiki is accomplished by first joining with the motion of the opponent (the physical aspect) as well as the intent (the mental portion), and then overcoming the will of the opponent, redirecting their move and intent.

Historically, this principle was used for destructive purposes; to seize an advantage and kill one'southward opponent. The modern fine art of aikido is founded upon the principle that the command of the opponent achieved by the successful application of aiki may be used to defeat one's opponent without harming them.

Attitude [edit]

Kokoro (心:こころ) is a concept that crosses through many martial arts,[ commendation needed ] but has no single discrete meaning. Literally translating as "heart", in context it tin can likewise mean "character" or "mental attitude." Character is a central concept in karate, and in keeping with the practise nature of modern karate, there is a great accent on improving oneself. Information technology is oft said that the art of karate is for self-defence; not injuring i'due south opponent is the highest expression of the art. Some popularly repeated quotes implicating this concept include:

- "The ultimate aim of Karate lies non in victory or defeat, but in the perfection of the grapheme of its participants." -Gichin Funakoshi[10]

Budō [edit]

Literally 'martial way' is the Japanese term for martial fine art.[xi] [12] [13]

Bushidō [edit]

A code of honor for samurai manner of life, in principle similar to chivalry merely culturally very different. Literally "the way of the warrior", those dedicated to Bushido have exemplary skill with a sword or bow, and can withstand corking pain and discomfort. It emphasizes courage, bravery, and loyalty to their lord (daimyō) above all.

Courtesy [edit]

Shigeru Egami:[14]

Words that I take ofttimes heard are that "everything begins with rei and ends with rei". The word itself, withal, can be interpreted in several ways; it is the rei of reigi meaning "etiquette, courtesy, politeness" and it is as well the rei of keirei, "salutation" or "bow". The significant of rei is sometimes explained in terms of kata or katachi ("formal exercises" and "grade" or "shape"). It is of prime importance not just in karate just in all modern martial arts. For the purpose in modern martial arts, let us understand rei equally the ceremonial bow in which courtesy and decorum are manifest.

He who would follow the way of karate must exist courteous, not only in preparation but in daily life. While humble and gentle, he should never be servile. His performance of the kata should reverberate disrespect and confidence. This seemingly paradoxical combination of disrespect and gentleness leads ultimately to harmony. It is true, as Principal Funakoshi used to say, that the spirit of karate would be lost without courtesy.

Kiai [edit]

A term describing 'fighting spirit'.[ commendation needed ] In practical utilise this often refers to the scream or shout fabricated during an attack, used for proper breathing likewise as debilitating or distracting the enemy.

Hard and soft methods [edit]

The "yin-yang" symbol (Chinese: taijitu).

In that location are two underlying strategic methodologies to the application of force in Japanese martial arts. One is the hard method ( 剛法 , gōhō ), and the other is the soft method ( 柔法 , jūhō ). Implicit in these concepts is their separate but equal and interrelated nature, in keeping with their philosophical relationship to the Chinese principles of yin and yang (Jp.: in and yō).

The difficult method is characterized by the direct awarding of counter-force to an opposing strength. In practice, this may exist a directly attack, consisting of movement directly towards the opponent, coinciding with a strike towards the opponent. A defensive technique where the defender stands their ground to block or parry (directly opposing the attack by stopping it or knocking it aside) would be an instance of a hard method of defence force. Hard method techniques are more often than not conceptualized as existence linear.

The soft method is characterized by the indirect application of force, which either avoids or redirects the opposing forcefulness. For example, receiving an attack by slipping past it, followed past adding force to the aggressor's limb for the purpose of unbalancing an assaulter is an example of soft method. Soft method techniques are by and large conceptualized as being circular.

These definitions give rise to the often illusory distinction between "hard-manner" and "soft-fashion" martial arts. In truth, most styles technically practice both, regardless of their internal nomenclature. Analyzing the difference in accordance with yin and yang principles, philosophers would assert that the absence of either 1 would render the practitioner's skills unbalanced or deficient, as yin and yang solitary are each only one-half of a whole.

Openings, initiative and timing [edit]

Openings, initiative, and timing are deeply interrelated concepts applicable to self-defence force and competitive combat. They each denote different considerations relevant to successfully initiating or countering an set on.

Openings ( 隙 , suki ) are the foundation of a successful set on. Although possible to successfully injure an opponent who is ready to receive an attack, it is obviously preferable to attack when and where one's opponent is open. What information technology means to exist open may be as blatant as an opponent condign tired and lowering their guard (as in physically lowering their easily), or equally subtle as a momentary lapse in concentration. In the classical form of combat between masters, each would stand nearly entirely motionless until the slightest opening was spotted; only then would they launch every bit devastating an attack as they could muster, with the goal of incapacitating their opponent with a unmarried blow.[xv]

In Japanese martial arts, "initiative" ( 先 , sen ) is "the decisive moment when a killing action is initiated."[sixteen] There are two types of initiative in Japanese martial arts, early on initiative ( 先の先 , sen no sen ), and late initiative ( 後の先 , go no sen ). Each blazon of initiative complements the other, and has different advantages and weaknesses. Early on initiative is the taking advantage of an opening in an opponent's guard or concentration (run into suki, supra). To fully take the early on initiative, the attack launched must be with total commitment and lacking in any hesitation, and nearly ignoring the possibility of a counter-set on past the opponent. Late initiative involves an active attempt to induce an attack past the opponent that will create a weakness in the opponent'south defenses, often by faking an opening that is too enticing for the opponent to pass up.[16]

All of the above concepts are integrated into the idea of the gainsay interval or timing ( 間合い , maai ). Maai is a complex concept, incorporating not just the distance between opponents, but besides the time information technology will take to cross the altitude, and angle and rhythm of assail. It is specifically the verbal "position" from which one opponent can strike the other, after factoring in the to a higher place elements. For example, a faster opponent's maai is farther away than a slower opponent. It is platonic for ane opponent to maintain maai while preventing the other from doing so.[17]

The Three Attacks

- Go no sen - meaning "tardily assail" involves a defensive or counter movement in response to an attack.[18]

- Sen no sen - a defensive initiative launched simultaneously with the set on of the opponent.[18]

- Sensen no sen - an initiative launched in anticipation of an set on where the opponent is fully committed to their attack and thus psychologically beyond the signal of no return.[18]

Shuhari [edit]

The principle of Shuhari describes the 3 stages of learning.

States of mind: empty, immovable, remaining, and beginner's [edit]

Pedagogy [edit]

Schools [edit]

Literally meaning "flow" in Japanese, Ryū is a particular school of an art. U.Due south.A. school of Japanese martial arts.[ commendation needed ]

Instructors [edit]

Sensei ( 先生 ) is the championship used for a instructor, in a similar manner to a college 'Professor' in the United States. Sōke ( 宗家:そうけ ) translates equally "headmaster" meaning the head of a ryu.[ citation needed ]

Seniors and juniors [edit]

The relationship betwixt senior students ( 先輩 , senpai ) and inferior students ( 後輩 , kōhai ) is one with its origins not in martial arts, but rather in Japanese and Asian civilization mostly. It underlies Japanese interpersonal relationships in many contexts, such as concern, schoolhouse, and sports. It has get part of the teaching process in Japanese martial arts schools. A senior educatee is senior to all students who either began preparation after him or her, or who they outrank. The role of the senior educatee is crucial to the indoctrination of the junior students to etiquette, work ethic, and other virtues important to the school. The junior student is expected to treat their seniors with respect, and plays an of import office in giving the senior students the opportunity to learn leadership skills. Senior students may or may not teach formal classes, only in every respect their role is as a teacher to the inferior students, by instance and by providing encouragement.[nineteen]

Ranking systems [edit]

There are ultimately two ranking systems in the Japanese martial arts, although some schools have been known to blend these two together. The older organization, usual prior to 1868, was based a series of licenses or menkyo. There were generally very few levels culminating in the license of total transmission (menkyo kaiden).

In the modern arrangement, commencement introduced in the martial arts through judo, students progress by promotion through a series of grades (kyū), followed by a series of degrees (dan), pursuant to formal testing procedures. Some arts use simply white and black belts to distinguish between levels, while others use a progression of colored belts for kyū levels.

Forms [edit]

It has often been said that forms (kata) are the backbone of the martial arts. Nevertheless, different schools and styles put a varying amount of emphasis upon their practice.

See too [edit]

- List of Japanese martial arts

- Okinawan martial arts

Sources [edit]

Hall, David A. Encyclopedia of Japanese Martial Arts. Kodansha The states, 2012. ISBN 1568364105 ISBN 978-1568364100

References [edit]

- ^ Green, Thomas (2001). Martial Arts of the World: Encyclopedia. pp. 56–58. ISBN978-1576071502.

- ^ a b Mol, Serge (2001). Classical Fighting Arts of Japan: A Consummate Guide to Koryū Jūjutsu. Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha International, Ltd. p. 69. ISBNiv-7700-2619-6.

- ^ Armstrong, Hunter B. (1995). The Koryu Bujutsu Experience in Kory Bujutsu - Classical Warrior Traditions of Japan. New Jersey: Koryu Books. pp. xix–20. ISBN1-890536-04-0.

- ^ Dreager, Donn F. (1974). Modern Bujutsu & Budo - The Martial Arts and Ways of Japan. New York/Tokyo: Weatherhill. p. 11. ISBN0-8348-0351-8.

- ^ Fri, Karl F. (1997). Legacies of the Sword. Hawai: University of Hawai'i Press. p. 63. ISBN0-8248-1847-iv.

- ^ Oscar Ratti; Adele Westbrook (15 July 1991). Secrets of the Samurai: The Martial Arts of Feudal Nihon. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN978-0-8048-1684-7 . Retrieved eleven September 2012.

- ^ Skoss, Diane (2006-05-09). "A Koryu Primer". Koryu Books. Retrieved 2007-01-01 .

- ^ Warner, Gordon; Draeger, Donn F. (2005). Japanese Swordsmanship. Weatherhill. pp. 8–9. ISBN0-8348-0236-8.

- ^ "World Shorinji Kempo Organization". World Shorinji Kempo Organisation. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ Ribner, Susan; Richard Chin (1978). The Martial Arts. New York: Harper & Row. p. 95. ISBN0-06-024999-4.

- ^ Morgan, Diane (2001). The Best Guide to Eastern Philosophy and Religion. New York: Renaissance Books. p. 38.

- ^ Armstrong, Hunter B. (1995). The Koryu Bujutsu Experience in Kory Bujutsu - Classical Warrior Traditions of Japan. New Jersey: Koryu Books. pp. nineteen–20. ISBN1-890536-04-0.

- ^ Green, Thomas A. and Joseph R. Svinth (2010) Martial Arts of the Globe: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation. Santa Barbara: ACB-CLIO. Page 390. ISBN 978-ane-59884-243-two

- ^ Shigeru, Egami (1976). The Middle of Karate-Practise. Tokyo: Kodansha International. p. 17. ISBN0-87011-816-1.

- ^ Hyams, Joe (1979). Zen in the Martial Arts. New York, NY: Penguin Putnam, Inc. p. 58. ISBN0-87477-101-3.

- ^ a b Lowry, Dave. "Sen (Taking the Initiative)".

- ^ Jones, Todd D. "Angular Set on Theory: An Aikido Perspective". Aikido Periodical. Archived from the original on 2009-01-22.

- ^ a b c Pranin, Stanley (2007). "Exploring the Founder'due south Aikido". Aikido Journal. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-07-25 .

- ^ Lowry, Dave (1984). "Senpai and Kohai (Seniors and Juniors)". Karate Illustrated.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_martial_arts

Postar um comentário for "What Is the Correct Name of the Original Japanese Art of Jujutsu?"